A Personal note1

“A human environment cannot exist apart from nature, and so agriculture must be made the foundation for living. The return of all people to the country to farm and create villages of true men is the road to the creation of ideal towns, ideal societies and ideal states.” (Masanobu Fukuoka – in – The Natural Way of Farming).

What inspired me to go back to my ancestral village in the eighties was the dream of “One straw revolution” of Masanobu Fukuoka, the need for alternatives to the present paradigms of modern science, development and polity raised by Rajni Kothari, Dhirubhai, Ashish Nandy, Vijay Pratap and other sensitive and eloquent social scientists of Lokayan, the urge to do something – crystallizing the ideas (into action) by Uma Shankari, my wife, and my father who was a government servant all his life, but a farmer at heart. He increasingly took the driver seat once we moved to the village!

A cocktail of social work, farming and research has not taken me very far in finding solutions to the problems (or challenges) in the agriculture sector. But it has certainly made me more aware of the complexity of the variables involved, their interconnections and contradictions. Before finding ‘solutions’, to recognize situations for what they are. I now feel more at sea than when I began – fourteen years ago( in1987) – having gone back to my ancestral village and ancestral property of 36 acres in Venkatramapuram of Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, 65 kms. from the religious centre of modern Hindu India – Tirupati.

Some of these dilemmas are:

Is natural/organic farming a viable proposition?

How does one meet the cash needs through organic farming?

How to make it less laborious? And yield more?

Or should we simply say “agriculture into economics won’t go?”

• Accepting the unsustainable nature of modern farming of chemicals and pesticides, how does one cope with the short term need to feed starving millions? But for the high yielding varieties of the green revolution, would it have been possible for our country to become reasonably self-sufficient in food and get out of the clutches of the food-politics of U.S.A.?

• Haven’t all societies in the past, feudal, capitalist or socialist based themselves on extraction of surplus value from agriculture and utilizing the same for development in other spheres especially industrial? How then are we thinking of a society in which agricultural surplus is minimal and terms of trade are in favor of agriculture and the countryside?

• Can we stop the genetically modified foods/seeds from swamping the market? Especially if they are going to be cheap and plentiful. at least to start with?

• Are we underestimating or ignoring human tendency to try and do with less effort to relax from any activity regarded as ‘work’? To consume ‘new’ things? Of wanting to bite the forbidden fruit? To innovate, to rebel?

• If foreign agricultural products (or any product for that matter) are going to be cheaper, what harm is there in allowing their imports? Will it not be good for the consumer and will it not propel the producer in our country to look for ways to make his produce cheaper? To improve yields and efficiency?

• Isn’t producing for personal gain a more efficient and rational way of organizing production and sale than co-operative/collectivized effort? Aren’t these the lessons from our own experience and that of USSR and China?

• How far is it practicable to combine the efforts of agricultural workers and farmers on their demands?

• Is it possible to organize farmers on a national-international level?

• Are land reforms a thing of the past? How far can parcelling of land go?

How far are caste and untouchability impediments to agrarian mobilization?

In the following narrative I shall try to address some of these dilemmas and the challenges we have faced and continue to face in the course of the last fourteen years of our stay in our village here, recognizable by our weakening eyes, graying hair, and growing children. We have been trying our hand at organic farming and chemical-pesticide farming, trying to make our farming viable and not really succeeding; trying to organize the farmers on issues like increased power charges (7 times at one stroke), the WTO imports; assisting agricultural workers, especially dalits on the question of untouchability, land reforms, and access to tamarind trees; helping the bamboo workers to form a co-operative society; trying to kick up enthusiasm for local health traditions and ayurveda; we only seem to be running in circles, if at all…….

It is therefore necessary to do some introspection and reflection on what changes have occurred and are taking place, why are we doing what we are doing and why is there no adequate response or why are people responding the way they are. I have broadly divided the narrative in to three sections: The first part deals with our battles (long live Don Quixote) in organic and inorganic farming. The second part deals with the problems of the agricultural workers and dalits. In the third part an attempt is made to reflect on the issues at a more general level.

PART – I

“In a sense, farming was the simplest and also the grandest work allowed of man. There was nothing else for him to do and nothing else that he should have done.” (Masanobu Fukuoka, The Natural way of Farming).

That is easier said than done! Fukuoka is not talking (p.258) just about farming the way we normally understand it. Through that activity which we generally think of as farming he discusses a whole way of life and thinking that seems to go against the present way of doing things. The question that bothers me is .. this materialistic orientation (in the pejorative sense), obsession with productivity and profits, the consumerist culture… is this something special to the present era or to what extent is it all a part of human nature? For after all haven’t saints and seers from Buddha and Mahavir downwards to Gandhi, Marx and Mao said something similar?

Coming to Indian agriculture, according to Rajini Palme Dutt: “It was during the first three quarters of the 19th century that the main ravages of Indian industry took place, destroying formerly populous industrial centers, driving the population into villages and destroying equally the livelihood of millions of artisans in the villages.” (Palme Dutt, R, India Today, PPH, Bombay 1947, p.225-226).

So that the proportion of the population dependent on agriculture rose from 61% in 1891 to 73% in 1921 (Central Banking Enquiry Committee – 1931) and has more or less remained at that level for the next fifty years (73.8% in 1971) but fallen slightly to 68% in 1991. In other words there is extreme pressure on land due partly to the de-industrialisation policy followed by the colonial rulers. This has been accentuated by the policies of our rulers ever since independence in trying to extract the surplus from agriculture and invest it in industrialization. The adverse terms of trade for agriculture sector and consequent poor performance of the industries have only worsened the situation. The share of agriculture in the GNP has been consistently falling from 60% in 1947 to 31% in 1991. A more telling figure is that the per capita availability of food grains in 1905-06 was 549 gms/day which in 1986-’87 was only 470 gms/day rising slightly in 1993-’94 to 491 gms/day.

“The most alarming feature, as regards the future of our agriculture is, that capital formation in the farm sector, as a percentage of the total in the country, has now (1997-’98) sharply declined to less than 8% as compared to 18% in 1980-81. Capital is attracted towards those ventures, which yield high returns. Sharp decline in capital formation in the farm sector is a clear evidence of its poor profitability”. (see Annexure – I).

“…..the disparity ratio between per capita average income of agriculturists and non-agriculturists is now (in 1997-’98) 1:5.5. In 1950-’51 this ratio was only 1:2.2. Such fast growing disparity in incomes is neither conducive to faster growth in agriculture, nor even to maintenance of peace and tranquility in the country.” (Bhanu Pratap Singh: ”Indian agriculture on the decline” reproduced in Souvenir of Andhra Pradesh Federation of Farmers Associations, Hyderabad, Feb 2001.)

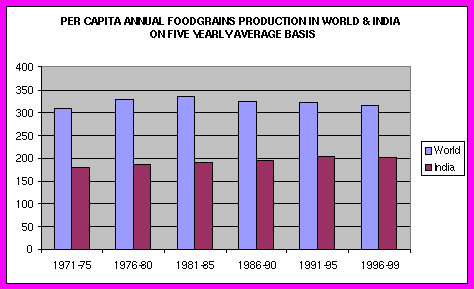

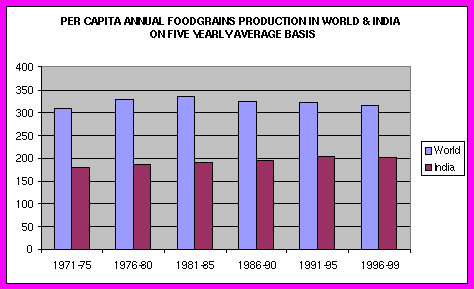

“The green revolution was only a 10 years phenomenon, created under the impact of two factors, first, the introduction of high yielding variety seeds, and secondly the then prevailing terms of trade, which were favourable to agriculturists. If we compare the five yearly averages of food grains production (five yearly average will even out the vagaries of nature ) in 1949-54 and 1964-’69 i.e. during the pre-green revolution period, we find that the growth rate of food grains production was 2.66% per annum. During the 10 years green revolution period, 1964-69 to 1974-’79, the growth rate was 3.34% per annum. During the 20 years of post green revolution period 1974-’79 to 1994-’99 the growth rate has been only 2.49% per annum… And during the last eight years 1990-’91 to 1998-’99, on annual production basis, growth in food grains production has lagged behind even the growth in population” (see Annexure-II).

“The share of agriculturists in the national income is now (1998-’99) no more than about one-fourth, while they still constitute nearly two-third of the population of the country. The share of industrial sector in the national income has also been declining in recent years. It is the service sector, which really produces no tangible goods, but which now corners more than 51% of the national income, and provides employment to no more than 17.2% of our total population. Simple calculation shows that the average per worker income in the service sector is now about eight times the average income of agriculturists.”

(see Annexure – III) (From: Bhanu Pratap Singh - “Indian Agriculture on the Decline.”)

“Inspite of all these achievments (of increases in yield and production) scores of farmers are committing suicides in AP. In Chittoor district where I live, farmers are a weary, tired lot today. Whatever they may do they seem to be in losses. The feeling of frustration and resignation is all - pervasive; the sense of inferiority is profound. Farmers introduce themselves apologetically, much like the women who introduce themselves as “just housewives.” (Uma Shankari, “Farming in Andhra Pradesh : A Ring side View” paper presented at NAPM Workshop on 2-3-2001 at Hyderabad).

In this background I shall try to describe the farming practices in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh and our battles amidst them.

Crops in Chittoor District: Traditional and modern:-

Around 70% of the lands in Chittoor district are dry lands and rainfed crops are grown on them. Only 30% is irrigated as against the Andhra Pradesh average of 35%. Earlier a variety of dry crops – millets, ragi, bajra, jowar, and dry crops such as ground nut, red gram, cowpea, bean pea, horse gram, etc. used to be grown. But due to unremunerative prices for millets and dry crops people have more or less ceased raising them and have instead concentrated on ground nut which is by far the most remunerative of the lot (of late in the last 2 years due to imports of cheap palm oil from Malaysia the prices of ground nut oil and coconut oil have also crashed.)

As a part of the Eastern ghats most of the district is studded with hills. Traditionally, several chains of small tanks have been built, especially during the reign of the Vijayanagara kings and these form the backbone of irrigated agriculture in the district in the absence of any major river or canal projects.

The farmers in our area ( which is the middle part of the district) grow paddy for one season and follow it up with two years of sugarcane. This is the cycle. In the eastern taluks of our district the situation is somewhat different. There the soil is more sandy and there is more rainfall. Farmers opt for a cycle of paddy and groundnut (in rabi). In the western taluks, the climate is moderate, but there is water shortage although the soils are red and rich. They prefer to grow vegetables, especially tomato. While some do grow mulberry (for silk), the location of two metropolis close by, Bangalore and Chennai (175 kms and 150 kms respectively from Chittoor) has spurred the growing of vegetables like tomato, brinjal, beans, and potato apart from flowers and grapes in a few pockets. It has also meant rapid growth in allied activities such as poultry and dairying.

The district enjoys cover of both monsoons. It gets about 900 mms of annual average rainfall. The salubrious climate and easy drainage of water in most areas enables the farmers to raise a variety of crops from pan and banana to sugarcane, paddy, groundnut, flowers and vegetables as mentioned above.

Jaggery: The district is known for its jaggery. The jaggery comes in two categories, the white or golden yellow colored, mostly from Aragonda or western region is for consumption.. and fetches a better price. Farmers have increasingly taken to adding bleaching agents such as sodium hydrosulphate, (Hydros) which is prohibited for human consumption. The colour lasts for a couple of months, by which time the jaggery changes several hands and is also probably consumed. The second variety is of darker even black colour due to the nature of the soil. Generally soils which are alkaline will give rise to paler jaggery, which though attractive to look at is not as sweet as the darker one. The latter fetches a slightly lower price than the yellow variety (by about Rs.100/- to Rs.200/- per quintal). It is mostly meant for brewing illicit liquor.

A number of private sugar factories have sprung up in the district, apart from the two major cooperative sugar factories sponsored by the government. As there is enough cane to supply the factories there is no restriction on production of jaggery, which often fetches a better price than the factory price for cane. Besides, the farmers do not have to run after the factory sugar cane inspector for the cutting order and then wait for the lorry to arrive at any odd hour and search for people to load it with cane. Farmers appear least bothered about their jaggery being used for brewing arrack.

Prices of jaggery and sugarcane (factories) have been more or less stagnant for the last five years while the cost of production, labour, fertilizer, and electricity etc. have been steadily going up.

Mango: Climatically the area is suited for mango. Once a mango garden is raised (in about 7 years) it requires little maintenance and fetches fairly good income – about Rs.10,000/- per acre. While the income from mango for the last three decades has been steadily rising, the costs have also started rising, especially for spraying pesticides and irrigating and of late, the returns are not as much as they used to be earlier (a decade ago). Although the price of mango is highly volatile from year to year depending on the production in the district and elsewhere, it tends to give a steady income in a lump sum annually to the farmer with least maintenance problems. Most farmers sell their mango crops to merchants for one or two years at a time and use the money for some urgent needs such as marriages, house construction or sinking bore wells or for medical bills. A number of juice making factories have sprung up in the district (around 25) which are seasonal in operation. Their fortunes also fluctuate with the mango market. (See Annexture IV)

Vegetables: The highly volatile vegetable market is very labour and capital intensive and farmers prefer to grow them in small plots of one or two acres generally. Vegetables and sugarcane crops are the mainstay of small and marginal farmers. As there aren’t enough cold storage plants farmers are often put to heavy loss in vegetables, especially tomato, when the prices crash due to a glut in the market. The stakes are high for tomato with investments ranging from 25 to 40,000/- per acre with profits likely to go up to even one or two lakhs per acre (if tomato sells at Rs.10 or Rs.12/-) per kg in the whole sale market).

Groundnut: It is the main stay of the dry land farmers, and most marginal farmers double up as agricultural workers. Unfortunately, the crop is very much dependent upon the mercy of timely and frequent rains in the kharif. For every one season of good crop there will be two bad years of heavy loss and two years of bare sustenance. Of late, the cost of raising groundnut crop is also rising, pushing the farmers into greater debt. The brunt of the price crash due to import of cheap palm oil from Malaysia was borne by these farmers. The yields are also very low --- depending on timely rains, from 5 to 15 bags an acre. But the economics in the flat sandy soils of the Eastern taluks of the district are very different where it is raised as an irrigated dry crop in the rabi season with heavy doses of chemical fertilizers, the yield going up to 30 to 40 bags per acre, if not more.

Choice of crop :

Price or profit is the basic motivating factor for the farmer to grow any crop. But he will make the choice of crop depending upon a variety of factors apart from the price, like cost and easy availability of labour in season, ability of the crop to withstand shortages of water supply and easy marketability, disease- proneness of the crop. It is the risk of rejection by the factory (apart from the intensity of labour) that dissuaded many farmers from taking to gerkin cultivation under contract farming for a company in Kolar, Karnataka, although it promised high returns of Rs.50,000/- per acre apart from supply of seed, pesticide, fertilizer and credit and buy-back of the produce at a fixed, predetermined price. It is for the same reasons that crops like sugarcane are preferred to the rest: sugarcane can withstand shortage of water for over a month i.e. even if one or two wettings are missed or even more it will still give some crop unlike say paddy or vegetables which will be wiped out. One gets nothing, besides it is least disease prone and jaggery making can be managed with family labour with one or two labourers, so that even at current low prices,( not counting family labour) one can earn up to Rs.20 to 30,000 per acre (gross income). If dairying can take care of the running costs of labour, etc. then one can end the season with a lump sum. This is the main attraction of sugarcane.

Two cheers for tenancy : We were surprised to hear that my grand father and my uncles would never give their land on lease /tenancy/share cropping. They always cultivated with the help of farm servants, family labour, and hired labour. But today the scene is completely different. Almost all the farmers under our tank (10 out of 12) with lesser extent under each are giving their lands for share cropping. The non-remunerativeness of most crops especially paddy, the problems of ensuring labour supply when needed in season, power supply, etc. have prompted many farmers to go in for tenancy farming even if they have small holdings of one or two acres. Often they give a part of their land, usually 1/3rd acre to 2/3rd acre to a tenant (by oral agreement) and cultivate the rest by hired labour using the tenant to water their lands and to organize other operations, such as, calling labour, making jaggery for the owner (his labour is costed) but assures the farmers of labour for making jaggery. By this method the farmer’s income is halved and would imply a net income of Rs.10,000 to 16,000/- per acre for sugarcane/jaggery and 10 to 15 bags of paddy per crop per acre. This way the farmer really benefits in paddy cultivation. If he had to do it through hired labour he would end up with heavy losses. But farmers cultivate paddy so that they don’t have to buy rice which can become quite an expensive proposition, and secondly, through raising paddy the soil is enriched with organic nutrients making it ready for growing chemically fed sugarcane and vegetables for the next one or two years besides providing straw for the cattle.

For almost similar reasons, the agricultural worker opts for tenancy, since he has no land of his own (with water) and there are many like him. By raising paddy (and supplemented by the subsidized ration rice) he is able to meet his rice requirement without having to go to the open market. He does not hire labour, usually making do with a little exchange of labour with his neighbouring tenants. If he were to cost all this labour he would be worse off. He would be actually making a loss. But he too prefers tenancy as it assures him of rice and hay for his cow and bullocks and an assured sugarcane crop for two years. Usually, he would have borrowed money from the farmer (often without interest), the farmer in turn borrowing from the jaggery merchant (at an interest of 18 to 24%).

The missing cheer: Giving a part or the whole of one’s land on tenancy does not solve the land owner- farmers’ problems altogether. The tenant after the initial heavy schedule of preparing the land and planting paddy or sugarcane, has to only do watering most of the time. He prefers to do this at night and go for daily wage during the day which can fetch him any where between Rs.40 to Rs.60/- so, the farmer owner has to always keep a watch on whether his fields are being irrigated properly, whether deweeding and fertilizer application have been done on time and properly, and to ensure that timely and proper spraying is done especially for paddy and vegetables and crushing of cane for jaggery production started in time before the onset of power shortages in summer.

Labours’ love lost: The other problem with labour is that they are forever demanding money in advance, promising to come for work. Having used up the money they then try to avoid the person from whom they have borrowed. It is often in such a situation that farmers/ money lenders physically assault the agricultural workers. The workers on the other hand, unable to make both ends meet (some of them are into drink as well) tend to borrow from several land owners promising to come for work. A lot of hide and seek goes on with the workers preferring to go to work for those who are likely to pay immediately. So the lesson is to try and pay immediately after the work is done and not to give advances/loans. But often this is a difficult choice because the workers prefer advances, and the farmer ends up giving a loan as well as paying afresh! Further, if the farmer himself puts in labour, the workers work better. If the farmer/owner stands around, they work a little less. If the farmer does not turn up at all, then they work even less – (20 to 30% less). Farmers lament that workers are no longer as hard working as they used to be. (That applies to the farmers also). They recall that in the good old days they would rise in the early hours around 2 to 3 a.m. and draw the water from the wells using bullocks and “Kapila” – a huge leather sack. In the “good old days” of course, the agricultural worker had little option but to work for the landlord or farmer, the children tending the cattle (now they go to school) and those who were truant (not turning up for work in time etc) were often beaten up. The farmers were also hard working (for they too had little choice of other avenues of earning money or survival). But now things have changed. With the advent of diesel motors and now electric motors, farmers and workers have got used to switching on the motors and since power comes with adequate voltage only at odd hours during the nights there is a tendency to flood irrigate using excess power and excess water (provided of course there is water in the wells). There are also apparently other avenues of work especially in urban areas although it is not easy to get.

The truancy of labour and their short supply when needed (in season), the alienation of both the worker and the owner from agriculture work, the worker / tenant because it is not his land and he would like to double as tenant (with least effort) and agriculture worker during the day, the farmer reluctant to put in the physical labour required and vexed with hired labour, unwilling to let go off the land; farmers are forever trying to do with less labour and looking for such devices such as switching over from labour intensive crops like paddy and vegetables to annuals like sugarcane and banana and from annuals to perennials like coconut and mango.

City lights and changing crops:

There is a growing trend, due to the strains and problems of agriculture, that those who are brighter (or even otherwise) will try to do something outside agriculture, either in allied businesses like selling fertilizers, jaggery, groundnut, mango business, running a petty shop or money lending. An enterprising person may do all of these or a combination of these. The children of the better off are educated often outside the village, in English medium schools and efforts are constantly on to help them settle down in urban areas where it is felt one can earn easy money. People also prefer to marry off their daughters to urban dwellers… the market rate being high especially for Government employees (for their assured income and side incomes).

When once a son is settled in business in an urban area or gets a job, the dynamics of his farm change. The family has to shuttle between the urban area and the village. They would thus prefer to raise crops which require less supervision and monitoring such as mango, coconut and such horticulture crops. So, sometimes they leave a small patch for growing rice for home consumption and convert the rest of the lands – the food growing area under tanks into mango and coconut gardens. This trend although very much visible in almost every village is some how not being assessed by the agricultural department. In a similar trend in Kerala, large tracts of paddy growing areas have been converted into rubber and coconut plantations.

Water is Life:

Agriculture makes one realize the critical importance of water. If there is timely rain as required periodically at different stages of growth and fruition of the crops, it makes all the difference – a single spell at times could be the difference between prosperity and desperation. The dry land farmer knows this better and more bitterly than anybody else. This is the reason why farmers, wherever they may be, are desperate to get an assured water supply for their lands. In upland areas, where there is little scope for river water through dams and canals, tanks supplemented by wells have been the backbone of irrigation i.e. assured water supply to crops. In Andhra Pradesh the traditional rulers over the centuries have constructed over 80,000 tanks some of them irrigating thousands of acres. In Chittoor district there are about 8,000 tanks today, mostly built during the rule of the Vijayanagara kings. Due to the hilly terrain most of them are chains of tanks with the surplus of one tank flowing into the one below and they are generally small in size irrigating between 30 to 100 acres. These tanks were often built and maintained by the ayacutdars themselves, who were encouraged to do so by the rulers offering tax concessions for several years. It was also thought of as an act of merit deriving “punyam” for those constructing the tanks.

An elaborate system of rules of maintenance and sharing of water were evolved - a part of the land and / or produce was set apart separately for the maintenance of the tank, all the ayacutdars at the beginning of the rainy season had to collectively clear the supply and feeder channels of weeds, etc. There was always a headman (“Pinapedda”) who was usually the one who owned most land under the tank. It was he who would give specific instructions for the actual activities to the Neergatti, who was invariably a Scheduled Caste person.

The Neerugatti, or water – irrigator was the critical person in the whole structure. It was he who irrigated all the fields, called the ryots for work, and repaired, especially at times of rains, when the bund could give away. When there is less water in the tank, he would intimate the ayacutdars. All the ayacutdars would assemble and decide what crops to grow. It was the job of the Neergatti to see that the tank water was distributed equally between those who were tailenders and those who had lands just below the bund. The neerugatti family was maintained by all the ayacutdars. He was entitled to a share of the produce and was also to be fed by the ayacutdars when irrigating their fields. There were many tax concessions for the ayacutdars and much of the tax collected from the tank irrigated lands often went back to the village for maintenance of the temple, tank etc. The king / ruler was supposed to collect a sixth of the produce. But this was increased to one-fourth during medieval times and to almost half during British rule as they did not understand any of these rules and simply transposed the British system. They would also tax the land and not the crop. As the tanks were declared to be Government property, the Government took away a major share of the produce. The ayacutdars were left with little surplus or motivation to maintain the tanks. This led to gross neglect of tanks and fall in revenues. And lands were even left fallow at times. The British set up various committees and realized their mistakes. But they were not willing to part with their over all claim to the ownership of the tank and share in the produce as taxes, although they reduced them a little. They took up maintenance of the tanks and found it to be a costly affair. They abandoned the smaller tanks and concentrated only on the bigger ones (above 100 acres ayacut). So the decline of tanks began during the British rule although the tanks were the heart of the irrigation in these dry regions and people did try to maintain them as best as they could under the circumstances, as there was no other means of irrigation except wells, which often supplemented the tanks during the rabi season. As the maintenance of tanks declined, well irrigation increased.

Borewell technology and the electricity tangle:

The advent of freedom saw no perceptible change in the attitude of the authorities. The Government was still considered the owner of the tank system (and other common property resources) and therefore the onus was on the Government to repair and maintain or not. This was more so with the bigger tanks. The advent of diesel engines in the early sixties meant that more water could be pumped out with less physical effort. The problem was further accentuated with the introduction of electric irrigation pumpsets and supply of cheap subsidized electric power during the 70s and 80s. With the earlier bullock drawn moats, recharge of the wells kept pace with the water drawn out. But with the diesel and the cheaper electric motors the water table in the wells was depleted faster than their capacity to recharge. This necessitated deepening of wells and use of rigs to blast the rocks. But very soon the water table went beyond the reach of the rigs and the farmers were forced to go in for inwell bores. If one struck good water in the bore inside one’s well, it only meant that the neighbour’s well would go dry and he would have to bore deeper. This kind of one upmanship has meant that water table which was around 40 to 50 feet went down to 200 feet by the early 1980s. Soon in-well bores of 4 ½ inches gave way to 6 ½ inches - surface borewells now going up to 400 feet and beyond, necessitating use of more powerful motors 7.5 to 10 H.P. and pumpsets of 7 to 12 stages to suck the water from deep down - implying greater use of electric energy.

The current scenario is that all landholders below a tank who were earlier irrigating their fields with tank water (supplemented by wells towards the end of the season) now irrigate the same lands with deep bore wells pumping water from 200 feet and more below the surface. In this process many bore wells have gone dry and water has not been struck in new places. The lucky few also survive for an average period of five years. Those bore wells under tanks would get recharged when there is water in the tank. But those in the open are left to the mercy of the ‘pathal Ganga’. Or so long as some one else does not strike a bore well in the same underground path.

On an average, a farmer would have spent Rs.1,00,000/- per well. (This is a modest estimate taking into consideration the cost of digging an open well, lining with stones, going in for electric motor, then deepening the well, blasting with rigs and sinking a bore well, installing a compressor or more powerful electric pumpset and then abandoning the whole thing and going in for a fresh surface borewell, which may or may not strike water. For the 20 lakh officially recognized services in the State for electric powered motor connections, the farmers would have spent on an average Rs.1 lakh per service - something like Rs.20,000 crores! Very little of it has come from the banks or other state agencies. As surveys among the suicide committing cotton farmers revealed, most of the credit (80 to 90%) availed of by farmers came from private sources at heavy interest. But the farmer still prefers to go in for bore-wells at such huge expenditure and risk because it makes eminent sense to him.

If a farmer were to spend Rs.50,000/- sinking a bore well and fixing a motor and were to irrigate one acre of land with the water (the average per bore well is about 2 acres in this area) by planting sugarcane he would be able to more or less clear his loan within two or three years ( by which time, if not in the next two or three years the bore well would have gone dry or flow depleted forcing him to go in for another bore well, much deeper this time.)

With the advent of bore well technology, the Pandora’s box has been opened, with each-one-for-himself-and-the-devil-take-care-of-the-rest attitude. Sinking of bore wells is not confined to lands under the tanks but to dry lands which are being converted into mango gardens on a large scale (something akin to the orange gardens of Maharashtra).

Those who buy lands are mostly rich people, those who have made their money in agriculture related business (like mango merchants) fertilizer dealers, contractors (small and big), and professionals from the urban areas (with some rural roots) and those urbanites wanting to convert their black money to white as there is no tax on agriculture. Farmers generally compete for small patches of land contiguous to their plots and often quote very high prices (wet lands cost around Rs.1,50,000 to Rs.3,00,000/- per acre and dry lands, Rs.15,000/- to Rs.40,000/- per acre). The whole sale-purchase taking place in a cloak and dagger fashion often resulting in a lot of bad blood and ill feelings with morals and values taking the last seat.

The individual oriented bore-well technology has further aggravated the problem of neglect of tanks and gradually, those having lands adjacent to the tank bed have started encroaching on to them, often sinking bore wells right in the tank bed and occupying large parts of the tank bed. Almost every other year the revenue authorities announce “last warnings” and at times even destroy some standing sugarcane crop but the process continues. At times these encroachers even divert the water from entering the tanks. Being locally powerful, there aren’t many who dare oppose them and incur their wrath.

To day, in most villages of Chittoor district there is no question of even drinking water if there is no electric supply. Thanks to the way the borewell technology has been used or allowed to be used today, the farmers in Chittoor district are completely dependent upon electric supply for their water needs. This is more or less the case in all the upland areas of the state as well as the country.

The farmers are finding the going difficult with the present prices of agriculture produce. Besides, with the floodgates of imports being opened under WTO conditionalities and the prices of various agricultural commodities crashing and subject to the whimsical nature of the international market, the situation is only likely to get worse. With over 10 million tones of sugar in stocks in godowns and another 50 million tones of paddy and wheat, with unremunerative prices for practically all agricultural products, the prospects are indeed bleak for farmers of our country. It is in this context that the farmers feel highly resistant to withdrawal of any subsidy – of power or of fertilizer. The state Government under Chandrababu Naidu is proclaiming that it would go ahead with reforms in the power sector meaning all subsidies would have to go. The farmers have been repeatedly pleading that the upland farms have invested over Rs. 20,000 crores in well irrigation in the last two decades and the government having failed to provide canal water should either collect water user charges at the same rate as for the canal water users - a nominal Rs.400/- per acre per annum, or give them the first right of use over the power produced by the damming of rivers viz. hydel power at the cost of generation which is not more than 20 paise per unit and the whole quantity of around 9000 MU would be adequate to take care of agricultural requirements in our state. The demand is that it is the moral duty of the state to supply water to the farmers of the upland areas especially since they have invested such huge amounts – and the state has benefited from the increase in the value of produce. Records show that between 1982-’83 and 1996-’97 area irrigated under tanks has gone down by about 50%; under canals, surprisingly, by 15% but under well irrigation including bore wells the area went up by 40% covering 42% of the total irrigated area, (up from 20% in 1982-’83).

The problem needs a multipronged approach. One man in one village created wonders in Maharashtra (Anna Hazare in Ralengaon Siddhe) and one organization in deserted Rajasthan brought back a dead river to life reconstructing the tanks (Rajender Singh and the Tarun Bharat Sangh).

The Emperor’s Clothes –

Watersheds/ Vana Samrakshana Samithi:

It is such success stories which give us hope that all is not lost. It appears to have inspired our dynamic Chief Minister to adopt the same for Andhra Pradesh with World Bank aid. Under the watershed management programme over 5000 watersheds were to be developed within a span of 4 years, each of them being allocated Rs.20 lakhs. We all know what happens when a lot of money is poured into a project. The smell of money (like blood) attracted the local sharks in the form of petty politicians of the ruling party who are local heavy weights who cornered several of them each (3 or 4). Forget water - milk and honey flowed in their homes within a brief span of about 3-4 years. Not to be outdone, some of the NGOs also jumped into the race and most of them now have a handful of watersheds each, some handed down after being messed up by the local bigwigs or the Government (so, now they have an excuse). Even those NGOs who were earlier involved in organizing the dalits especially on issues of land, have now veered round to water-shed development and Joint Forest Management (Vana Samrakshana Samithis).

The entire exercise has been reduced to a farce and the people are left with a fat bill in the form of a foreign loan! The basic idea of watershed was never properly explained and means of getting the people involved took a back seat, the projects were time bound and the money had to be finished. Those monitoring the show assessed that at least 10% of the water sheds were reasonably successful, in the sense that the actual works were completed and there was some involvement of the local people and one could see the water table in the area rising. These will be the show pieces for the evaluators, the lenders and the media to be taken around. Similar is the case with the JFM projects.

Though watersheds are an important component of the alternate exercise including revitalization of tanks (there was this strange argument by some Government officials that tank revitalization was not part of water shed management as the same was not mentioned in the programme! The issue was later clarified) several other steps also need to be taken.

The farmer’s keenness to grow water intensive crops like sugarcane and paddy has to be traced to reasonable returns and assured income that they tend to provide. So we have to try and involve combinations of cropping patterns which require less water and give reasonably attractive returns, low or medium level of risk and effort. Turning to horticulture or growing of forest related medicinal plants like amla are a few options. The neglect of dry land crops such a ragi, bajra etc have had a telling affect both on the nutrition level of people in the area and tendency to convert to water intensive crops. If only the prices of these crops were higher. In the mean time, peoples’ eating habits have also undergone a sea change. They no longer consume these dry crops (sajja, korra, jonna) having converted to subsidized ration rice with a little smattering of ragi powder thrown in, if at all. Eating rice is considered socially superior to eating ragi or jowar. We have been eating unpolished rice for the last 12 years but have not been able to persuade our neighbours and fellow farmers and workers to do so. Earlier they used to also eat only boiled rice, now that is used only for making idlies.

Usage of energy saving devices such as HDPE pipes for water suction, frictionless footvalves and more efficient pumpsets can help save up to 15% of energy consumed by irrigation pumpsets (if not more). Metering of all services, and costing the power supplied will automatically lead to conserving energy used and help control theft being shown as agricultural consumption. Encouragement to drip irrigation and digging ponds in the fields to conserve water run-off during the rainy season are methods that could be promoted by demonstrations and imaginative incentives to farmers.

As stated earlier, the basic motivating factor for the farmer, like any one else, is relatively easy money. Any crop or practice will be adopted, even if it means some effort and some risk provided the returns are sufficiently attractive. Tomato has become one such crop in the western taluks and generally sugarcane in wet areas at other places. Till recently silk production was also quickly adopted by the farmers. The import of superior quality Chinese silk at reasonable prices has been affecting silk production of late.

Planners will have to make their programmes attractive for the farmers – adequate to motivate them. A kisan credit card, is such a scheme wherein the farmer is not tied down to a particular activity for availing the loan, allowing him some freedom of expenditure. A recent success story has been the thrift scheme for women popularly known as DWACRA (Development of women and children in rural areas) under which groups of 10 to 15 women get together and save Rs.30/- a month (a rupee a day) and deposit the money every month for 6 months at the nearest bank in a joint account. After six months of such saving the bank (government) sanctions each of the members a loan of Rs.1,000/- each. The cycle is repeated a second time and then they are ready for a bigger loan of Rs.15 to 20,000/- for dairying etc. The scheme does not insist on the loan amount in the first two stages to be spent only on productive purposes and allows for consumption purposes as well. But after the first two rounds, the saving habit is ingrained and the women usually buy productive assets by the third round. The repayment rate has been as high as 90% unlike the earlier schemes (50 to 60%). There are now more than 3,50,000 such groups across the state with their savings in each village ranging from 25,000 to more than a lakh and the total amount in the state running to several hundreds of crores.

From the above discussion it is clear that even 10 acres of land without water, as happens in Anantapur and Mahboobnagar districts, dependent on rains, and usually growing groundnut or jowar dependent upon the highly unpredictable rainfall pattern (untimely rains are as bad as no rain) is not equivalent to one acre of wet land - land with an assured supply of water. An average income would be around Rs.10,000/- to Rs.20,000/- per acre for wet land and Rs.1000/- to 2,500/- for dry lands depending upon the crop and rain.

From our own calculations if we cost rent for land, interest on bore well sunk, risk factor, management expenses and farmers’ own labour, etc, costing all these would imply a net loss (in 1999-2000) for irrigated paddy of Rs.9,725/-; for irrigated sugarcane Rs.13,475/-; and Rs.125 for irrigated groundnut. But the farmer calculates only what he actually spends by way of cash and that way there is an apparent profit. Excluding rent on land, cost of sinking a well and management charges the farmer gets a “profit” of Rs.7,625 in sugarcane, Rs.4,575 in paddy, Rs.8,775 in groundnut (see Annexure IV)

For the various schemes of water and power conservation (to make farming less dependent on external forces and more sustainable) of the NGOs or the Government or of political parties, how does one get the local people to co-operate? In all the schemes about watershed management or VSS or tank restoration this key element is being left unanswered. The same goes for the power crisis being faced by the farmers, with the Gov’t threatening to forcibly collect the dues and withdraw subsidies and raise the power charges several times more in the coming few years, the farmers are complacently waiting for the blow to strike even after the situation and the Government’s intention has been explained to them loud and clear by the Finance Minister, Yashwant Sinha in his budget speech and the near unanimous resolutions passed at the Chief Minister’s Conference on 3-3-2001 chaired by the Prime Minister. Although farmers are frustrated and angry at the crash in prices and are partly aware of the real culprit - the WTO conditionalities and India’s unpreparedness, there is a kind of despondency - perhaps a result of repeated desertion by the leaders of the farmers’ movements into electoral politics.

This then is the challenge, how to mobilize the farmers to fight for their rights and to work together for their survival?

Our farm:

Our 36 acre farm is the joint property of three brothers. Two brothers reside in Hyderabad. For managing the show I was to take 36,000/- a year. We have 26 acres of mango garden which cannot run on a loss. In a lean year, when crop is low and / or price is low we barely manage without loss; otherwise we can make on average of one to one and half lakh rupees from our 100 year old mango garden (May my grand father rest in peace!) We have in addition 550 coconut trees, mostly planted by my father (who was then in Government service ) in far away Hyderabad, 580 kms ) whose yield was somewhat low, about 20 to 30,000 nuts per year and facing a water problem of sorts. We also have two patches of wet land totalling about 5 acres with assured water supply in one plot of 2 ½ acres and somewhat short in the other. We also have about ¾ acre of dry land.

How not to make money in farming:

After 8 years, I find my bank balance of 7 lakhs has completely disappeared. I am left with loans of Rs.2 lakhs (some of it from the 4 lakh Swadeshi fund we had created). Incidentally, people also owe me around that much. But there is not a scrap of paper to prove that. Someday, some of them may return the loans. For the outsider, simple arithmetic would show that forgetting the rest of the property, if I were to share the surplus from the mango garden with my brothers, I should be giving them at least Rs.30,000/- per year. But even that I was barely managing to do every alternate year! Where is all the money going? Admittedly, I am a bad manager alright. But still, I have been honestly trying, although not giving full time, but atleast between the two of us (me and my wife) somebody is there most of the time and on those rare occasions (twice or thrice an year) when both of us are out, our friends, Nagesh and his wife Aparna manage the show (more about them later). The only asset we have acquired after my coming to power (at the farm) is the possession of a power tiller at a cost of Rs.1,25,000/- (ably advised by friend Narayana now warming his heels in Timbuktoo, Anantapur district, Andhra Pradesh). The only saving grace about the tiller is that our own farm hands are able to handle it and we don’t have to depend on other vehicles for ploughing and small transport and of late even spraying. (We still need the bullocks on hire for furrowing and the big tractor for transporting more than a ton).

How did we manage to make so much loss? Year after year? Through our wrong assessments (mostly mine) we often undersold our mango crop (to middle men). Vexed with them we have been trying to harvest ourselves which makes you feel you were better off selling the crop!

Under the wise suggestion of Nagesh (borrowed from Uzramma) we decided to stop growing sugarcane and instead grow rice. On ethical grounds we opted out of sugarcane and went in for rice, which included apart from the high yielding variety of the Government, some traditional varieties of other nearby regions (Tamilnadu and Telangana). Again for ethical/ideological reasons, we refused to give our land for tenancy farming and tried to cultivate using hired labour. At one place we had given a small plot of 1/3 acre to a worker for his own use and another plot on share cropping. It was his job to call labour for the various activities and at another site we gave the worker a salary of Rs.600/- per month plus a plot of land in share cropping.

We ended up paying enormous amounts for labour for two acres. We had heavily invested in organic and leaf manure and groundnut cake which are labour-intensive operations and we ended up spending some Rs.16,000/-. Our paddy crop was an average yielder meaning as much as anybody else. Most of the farmers are also easy going. They do not select their seed carefully. They do not nurse the nursery (treat the seed etc.). They often plant late but try to make up with application of urea and / or NPK. While the crop of paddy we produced was almost equal to what most of the other farmers were producing (20 to 22 bags per acre, only very few produced 30 to 40), our costs were twice or thrice of others. I was particularly peeved by the way the dalit workers would bring in their bullocks (sometimes country cows doubling as bullocks) and would do light ploughing so that the bullocks don’t tire. In the end despite their collecting their full wage, the plot would have hardly been ploughed needing another round. Now a days, no farmer has bullocks all of them having switched over to cows and hiring tractors for their small ploughing needs and even bullocks for furrowing etc. So only some agricultural workers have bullocks, which are over worked in season. One pair, I remember collapsed in my field. This is what prompted me to go in for the power tiller for which unlike the other farmers we paid the full amount as we were not eligible for the 35,000/- subsidy. (We were perhaps the only non-subsidy clients for the machine). The tiller had its own set of problems and expenses but atleast the whole thing was under our control and we could plough the way we wanted although it increased our dependence on outside forces (mechanic, diesel etc.). Ultimately, the rice we grew was rather expensive and very exhausting as we had to take care of so many vagaries like truant labour, diseases, timely application of various organic inputs (searching for them), timely weeding, proper harvesting and drying and finally storing. We could avoid all this if only we had given our land on tenancy. Besides, if we hired labour we would have to cook the afternoon meal for them (whew!) and also hear complaints about how badly the meal was cooked. No wonder most small farmers, including those owning one or two acres of wet land, give their land on tenancy. We hardly sold any of the paddy we produced. Most of it was consumed by us and our workers hired for various works. After three years of such expensive experiments we decided enough is enough, and opted for share cropping like the others! There is indeed so much relief, especially for people like us who are not used to physical work.

The broken chain or how not to do organic farming:

It is in this context that one must assess the whole question of usage of chemical fertilizers, and pesticides as well as high yielding varieties. Farmers are aware that traditional seeds are less prone to diseases and they taste better but the yields are low. Farmers know that farm yard manure is better and so is green leaf manure for paddy. But where is the farm yard manure in that quantity? (See Annexure VII)The forests have gone, the cattle wealth has disappeared. Earlier the SC boys would graze the village farmers’ cows for a pittance in the forests, the cows were there mainly for dung and breeding bullocks. Now the SC boys go to school and to maintain a farm servant is very expensive (More than Rs.1,000/- per month). The economy has turned from bullocks to cows with the advent of milk marketing and hybrid cows. With the one or two cows they maintain, the farmers make a combination of FYM, leaf manure for paddy and follow it up with chemical fertilizer application – three tractorloads of farm yard manure and about 150 bundles of green leaf lopped from trees meant for the purpose are put in the fields at the time of ploughing followed by three bags of urea. Some apply NPK ( 17x17x17) as well. They follow up the paddy crop with sugarcane planting for which no or not much FYM is applied but use 3 bags of 17X17X17 per acre in our area. They get an average yield of about 35 to 40 tonnes of cane per acre.

The question that bothers me is why are farmers not taking to composting, vermicompost, etc. which are supposed to fill the void of lack of enough dung and also enrich the FYM? That question I better ask myself. Even after 14 years stay in the village and 8 years of directly being involved in farming I myself have not got down to it. For me the reasons are: to make compost one needs to have mud and leaf transported to the spot where the cattle are and where the dung is being heaped. This requires additional expense. I have no tractor which means I have to hire tractor and labour for the purpose. Now of course I have the tiller but where do I get the mud from?. Since most wastelands have been occupied, one has to go to the tank bed. One might as well put the tank mud and the leaf manure and the dung directly on the soil and they would get composted right there with lesser expense/trouble - so the argument goes. It is not easy to find labour when needed, besides this is additional work for the person who is tending the cattle, but perhaps all these are excuses not very convincing. I am still unable to understand why I can’t kick myself to get the vermicomposting going. That requires construction of a couple of sheds with pits to prevent rats and birds from entering.. Am I too busy/ lazy in other activities? I have no excuse to offer especially since these are worth trying and could have a demonstrative effect. Every year I plan and it goes by.

In our experiments with organic farming to use the word loosely, to construe all that goes without the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, we tried several varieties of traditional paddy seeds, as also high yielding seeds with heavy doses of organic manure,( 6 tractors of FYM per acre, +200 bundles of leaf manure + 3 bags of groundnut cake/other oil cakes at time of deweeding for paddy), but somewhere something is always going wrong. For one thing there aren’t too many tillers of paddy coming up, the same seeds with a little bit of urea at the time of deweeding seem to multiply the tillers. That seems to me at the moment the missing link in paddy cultivation - how to make the high yielding varieties respond to organic manure - perhaps vermicompost could do the trick. In the meantime, the cost of growing paddy organically is becoming prohibitive unless we produce enough surplus to sell.

After burning our fingers with self-cultivation of paddy, we, like other farmers around opted for share cropping initially with the condition that they practice organic farming and since they cannot put the additional farm yard manure we put the same at our cost, We also added three bags of groundnut cake +castor+pongamia cake per acre…but so far this too has failed. We felt it was being unfair to the share croppers, making them share the losses of our experiments, so this year we let go,and allowed the share croppers (each one on 1/3 rd acre) to grow with chemical fertilizers except for the small 1/3 rd patch that we were continuing with “self –cultivation”.

We were controlling various pest attacks with neem oil spray, azardichtin spray, Besharam decoction spray till last year. The last crop was paddy BPT 5204 variety harvested locally called Jeelakara masoora- which we had grown earlier organically.It caught a disease and that was it. Try as we might, we simply could not control the disease. It is of some consolation that those who practiced chemical farming also got poor yields! (about 20 bags an acre was our yield while they got about 22 to 25 bags). This is usually what consoles the farmers- that his neighbors are worse off than him!

Pesticides – the vicious cycle:

Talking about pesticides, we must discuss the mango in particular. Our area has been climatically suited for raising mango gardens and my grandfather with much forethought had converted several paddy growing areas to mango gardens around 100 years ago and he even did mango business making use of the railway line exporting to Bombay. Those days no pesticide was used. Nor was watering done. But now, since the last 40 years pesticides have entered the scene…starting with DDT, then briefly endrine, which has seen the pests become accustomed to them. Then the farmers switched over to endosulfan which lasted for nearly a decade and half; soon the pests, mainly hoppers and thrips, became resistant to that also. This was replaced by monocrotophos and sevin/carboryl which lasted for about 5 years to 10 years. Now for the last 5 to 10 years, synthetic pyrethroids are ruling the roost. They can affect the hormones of the plants and have deleterious side effects like shrivelled leaf, etc. but the farmers have little option. Pyrethroids were so cheap and one spray would do whereas the earlier procedure of using endosulphan for one dose and then following up with monocroptophos etc were not only costly but cumbersome. The evidence is clear that a pesticide lasts for a few years effectively by one spray and over a few years one has to take recourse to two sprays and then after a few years even that becomes ineffective when one is forced to go in for a new, more powerful pesticide and so the sequence goes on till now we are almost at a dead end. The scientists say synthetic pyrethroids so far are the last word in pesticides, they have nothing more powerful and we are using that now twice instead of a single dose earlier. Suddenly the scientists have made a quick about turn and since last season have started saying actually there does not appear to be the kind of adverse effects of synthetic pyrethroids as was expected and one can use them in correct dose. Some of them talk about integrated pest management (IPM) - you make a cocktail of neem extract and chemical pesticide or reserve the chemical pesticide of lethal dose as a last resort. By this method the farmer ultimately ends up with a fat bill! It always makes me wonder how scientists talk of heavy doses of fertilizers and pesticides in repeated doses totally unmindful of the economics!

As an organic farmer, or at least as someone desiring to do organic farming, I was in a dilemma, for the last eight years, since I was in charge of the farm should I stop using the chemical pesticides? We were not sure of the success of the organic methods of pest control, so that would mean putting at stake our main source of income. So we decided consciously not to go in for organic pesticides for the main garden of 23 acres but try the exercise in a separate 2 ½ acre plot. For the last seven years we tried almost everything that our organic friends suggested, we found neem seed kernel grinding and spraying rather cumbersome on a large scale and switched over to neem extract, Azardictin-spraying for over 4 years (earlier we tried neem-oil, neem cake extract, Besharam decoction etc,including diluted cow urine. We spent a lot of money and effort in the main garden trying to avoid synthetic pyrethroids spraying the equally bad endosulfan, monocrotophos and one year the horrible smelling acephate. All this because we had experienced the bitter results of pyrethroids, when we leased out our crop to some businessmen from Karnataka, they had sprayed fenvelerate, a powerful synthetic pyrethroid, along with a growth promoter which we came to know later, and the next year and the year after the trees looked so weak and shriveled.

So we can very well see that we are following a wrong path. The history of pesticide usage on mango clearly has drawn us to this repeated warning from Nature that you can’t beat / defeat the “pest” with more and more powerful pesticide after each round. In the end like “Bhasmasura” we may end up being consumed by the pesticide ourselves. As it is, the mangoes produced by our pesticide sprayed garden are having pesticide residues and are not fit for export to the west - those great masters who taught us to use these pesticides in the first place! These lessons of ineffectiveness of pesticides were brought home very powerfully by the suicides of the cotton farmers in the Telengana area of Andhra Pradesh. Yes, of course spurious pesticides, spurious seeds are a part of the problem but growing pest resistance to pesticides, conducive climatic conditions also have their powerful say in pest control (or non- control).

In our experience we found in one year, in small patches where we have mangoes within the coconut garden (2 ½ acre plot) we sprayed nothing and in another patch of 2 ½ acres we sprayed organic pesticides several times (3 – 4 sprays per season) and in the main garden we sprayed only chemical pesticides (excluding synthetic pyrethroids) and in all three, the result was the same! Meaning the yield was very low that year. There is a tendency in mango to give a bumper crop followed by a lean crop year after year. But this is not always true and several climatic factors have their say. Ultimately we have realized this.

“Science never does any more than mimic a virtual image of Nature that exists only in the human mind, so what it grasps is only an incomplete and inferior imitation of the real thing. I can assert here without the least doubt that anything created by man with scientific knowledge will always be inferior to nature. When one realizes just how wondrous a thing nature is one can only bow to it in humble acknowledgement. The moment we become humble before nature and renounce the self, the self shall become assimilated into nature and nature shall allow it to live. Even a small ego becomes capable of summoning great strength. It is enough merely to know this road and walk it each day.” (Fukuoka, M., The Road Back to Nature - Regaining the Paradise Lost, P.224.

Dairying: Milking who?:

Dairying is an important link in our farming (unlike Fukuoka’s). And we tried our hand at dairying. We employed one person to look after the cows at a measly Rs.600/- per month (which he would make up through the hearty meals three times a day at our house). We raised grass and bought groundnut cake every month along with rice bran. We often ran out of rice straw which sometimes we had to buy at great cost. Initially, we were thinking of raising some local breeds - the famous Punganur breed, which is now not traceable thanks to the extensive cross breeding. We settled for cross-bred cows with a greater percentage of the local/natural blood. We raised grass and the first couple of years we did not make any loss as we were using some of the milk for our home consumption and selling the rest. But gradually the price of oil cake began to rise. Initially it was the same price as the milk (7 years ago) but now milk sells at Rs.6.50 a litre while groundnut cake costs nearly twice as much at Rs.11/- or so and a farmer has to feed at least a kg of cake to the cow every day twice a day…so most farmers don’t go by the rules…they feed their cows on the grass that they gather from the fields and what they grow. During the 4 months since January, they feed them on sugarcane leaf and in lean months on groundnut leaf and horse gram leaf and so on… keeping buying cake and rice bran to the minimum given only to lactating cows. And then we started making losses. For the last three years we were spending Rs.10,000/- per year extra! This was unsustainable. So we retired our cow man (who anyway had to be retired as we had given him the job of looking after the cows as a stop gap arrangement) with a ten thousand rupees fixed deposit. As for our cows we decided the better thing would be to lease it out to another worker who offered to do so, staying in our garden, and taking 2/3rd of the payment from sale of milk and giving us 1/3rd. The 2/3 rd including the cake and bran etc, We pay for any sickness and we also give straw from our paddy crop and whatever crop residues we get. He in turn will have to give us all of the farmyard manure produced. This has been on for the last six months - let us see how far this will sustain.

In the meantime, what is saddening is the way the Government has killed the milk co-operative movement initially promoted by it. When the cooperative movement was at its peak, milk sales were high and did a lot for improving the farmers’ lot (despite whatever Claude Alvares might say, milk was never an essential item in the diet of people in this region. It was used for children, and for butter-milk). It took care of all the minor routine expenses. Elections to the cooperatives right from the village to the district level were a big political affair and even the fellow who was secretary of the cooperative at the village used to make a lot of money, taking a little extra milk officially for testing and asking people to pour over the brim of the litre measured, etc. The milk for testing would never be tested. The society dairy was soon reeking of corruption and they were unable to pay bills to farmers for milk supplied to them for over a year! After much agitation the bills were paid but the cycle repeated. At this juncture the Government allowed private dairies to operate, with our Chief Minister (in opposition then) taking a lead by starting a big dairy (Heritage Foods). The private dairies have formed a cartel and they do not raise the price of milk, despite their being several buyers (so much for the multi buyer model of the World Bank). Now one cannot see big dairies of milk producers, anywhere in our area because they are simply not economical. Selling milk as middlemen is! So farmers manage their cows by grazing them and feeding as little cake and bran as possible. This implies a decrease in milk yield but then the costs work out. Often the milk is also diluted.

As far as diseases were concerned people treated their cattle with traditional remedies. It was only when these failed that they resorted to the Government veterinary care which, just like allopathic treatment, is prohibitively expensive. Of course, there were outbreaks of dangerous diseases like anthrax and there are foot and mouth disease advertisements at every veterinary hospital. But nobody panics the way they are reacting in Britain and the West. Of course you cannot feed crushed bones and skull to vegetarian cows and expect nothing to happen.

Alternate energy – the crying need:

Along with our cattle we had also maintained a gobar gas plant which was giving enough gas for one meal with dung from three cows - not very efficient. It was a concrete dome type model, a Chinese model, we are told, which gave way after ten years. It developed cracks in the dome and we could not restore it much as we tried. So now we have cooking gas from the nearby town, so much for bio-gas. But the new janatha model introduced by the Government is smaller and more efficient. A small family is able to manage its cooking over it with two cows--- feeding four people. Two families in the village are having this. The others do not have either enough space or motivation although almost all families have at least one cow each.

The question that bothers me is why are gobar gas plants not picking up? Why are people in villages also wanting to have gas cylinders? Now an elaborate system has developed in every village around ours by which empty cylinders are transported to the nearest gas agent and replacement delivered for a fee (Rs.20/- per cylinder). The state Government has a scheme by which gas connections are given to women in the DWACRA groups. These often ended up at the houses of better –off farmers as gas costs money.

Of health and wealth:

The question of health and treatment of the sick also needs to be mentioned here. In our eagerness to promote cheap and local health traditions we also wanted to promote ayurveda. But as our core fund had diminished to a mere four lakhs even before we started, the amount we were willing to pay, Rs.2000/- per month to an ayurvedic doctor was not attractive enough to any doctor - even a fresh graduate! There are three RMPs at the central village close to our village. The nearest MBBS doctor is 10 kms away. An allopathic doctor-friend of ours started weekly visits. He would not want to give medicines and injections unnecessarily. Initially people did not respond to him. Slowly his friendly ways and his willingness to explain and listen, made him acceptable, and many patients go to him regularly nowadays. We were also handing out medicines - allopathic, homeopathic and ayurvedic as desired by the patient (the choice was mostly left to him/her), but patients nearly always preferred allopathic medicines because of their capacity to give immediate relief. This is what the RMPs told us too. That whatever medicine we administer it must give immediate relief. The rest of the real treatment can follow. We tried to give a refresher course to the RMPs through our doctor friend,. but after the first two classes they decided it was not worth the effort. The agricultural workers, especially, feel they cannot afford to lose a day’s labour/wages. So, they go in for quick relief treatment. If things get complicated they go to the nearby town or even Tirupati. Our doctor-friend for personal reasons, stopped coming but continues to give medical advice over the phone and sees the patients we send to him free of cost. It is indeed a great relief to have a doctor whom you can trust not to give unnecessary medicines, nor to recommend unnecessary examinations, to talk sympathetically and in a friendly manner to patients, not to fleece patients where doctors thrive on disease and ignorance. It must be remembered that getting checked up by the doctor is only half the story. When they go to town, however sick they may be, a movie is a must, as well as buying odd things. So the sickness comes in handy.

Unpolished is Uncouth:

While agricultural worker households are still uncontaminated by and large by tea and coffee, for most farmer households these have become compulsory, and by their standards a fortune is spent on these beverages every month. People also insist on having only polished rice. Our efforts to induce them to eat unpolished rice have been in vain. In fact, at times, especially when there are guests, we are forced to prepare meals with polished rice. Some times workers protest and refuse to eat our unpolished rice, so that we have had to cook separately for them.

One is also reminded of the village bus. People are willing to stand for hours rather than walk up a kilometre to the next stop.

Giving up isn’t every thing:

Before summing up the dilemmas in agriculture, I must mention Nagesh and Aparna, the US returned computer engineers, who want to lead a Gandhian life of self – sufficiency based on agriculture, who are living nearby. They have purchased their own plot, to have a “free hand”, turning down our offer of taking some of our land on lease. Ever since they bought the plot three years ago they have done anything but farming - running from the revenue officials to the court to the police to the village bigwigs. They were twice cheated out of the deals they almost clinched ( I was partly to blame for one at least). And the final deal was with a person who had exchanged a piece of land with his neighbour cum relative promising him the land but sold it to Nagesh. So the battle dragged on for months and years, till the neighbour sold his share to a third party who continues the battle! So much for buying land and farming. Yet they have courageously stuck on. They are perhaps the only couple to live in a dalitwada with this kind of purpose in mind. They are of course finding the going tough. Most people are not honest, irrespective of caste and class in the village. Most of the time people speak half-truths allowing themselves some space for manoeuver lest they change their minds later on. But in a crisis people do gather together. They find the life of this couple very odd and unexplainable. In the first place nobody had invited them to stay in the dalitwada! Now that they have adopted a baby girl from an orphanage, they find them even more queer, that Aparna did not want to go through the pains of labour and so she bought a child!

<

Finally it must be remembered that the farmers are a tired lot to day. Most of them are single – nuclear family households, the joint families are an exception nowadays. Since farming is a collective effort, the whole nuclear family is then put to tremendous strain, both physical and psychological. They are heavily burdened with debts and yet there is hope - may be the next crop will see us through. In any case there is little alternative to growing wet crops. So in great desperation when a well or a bore well runs dry, the farmer feels his lifeline has been snapped and he will move heaven and earth to sink another bore well. He will certainly not wait for a service to be given before installing a motor if water is struck. The Power board employees are very understanding and are willing to oblige for a fee of course!

PART-II

The world of the agricultural workers:

“ A person of courage to day is a person of peace. The courage we need is to refuse authority and to accept only personally responsible decisions. Like war, growth at any cost is an outmoded and discredited concept. It is our lives which are being laid to waste. What is worse, it is our children’s world, which is being destroyed. It is therefore our only possible decision to withhold all support for destructive systems and to cease to invest our lives in our own annihilation.” (Bill Mollison in Perma Culture, 199-).

The agriculture worker lives in his own world… a world shared by the farmer, more than anybody else, but still it is a world of his own. Unlike the farmer, the agriculture worker is more of a day-to-day living mind. There is little conception of saving or acquiring property (some of them do so, though rarely). When there is money, they tend to spend lavishly but are capable of missing a meal or two and surviving on precious little. Although they are living in the midst of agriculture they have to buy almost everything that they need or want - from rice, to oil, vegetables, soaps, clothes, sandals, medicines and now a days even electricity for the single bulb they use. Some have prospered, thanks to reservations, education, jobs in railways, working in the towns. But these are the odd balls.

Past and present

Compared to 40-50 years ago there have been tremendous changes in certain aspects and precious little in other ways. It is difficult to generalize, not even on a local scale. One has to continuously qualify the class of the agriculture worker with his caste, the region etc. But still there is something that sets the agriculture worker apart from the farmer. In our area almost all the workers have some piece of land, ½ an acre, mostly dry land on which they sow groundnut and sometimes even horse gram. The more enterprising even try out tomato during the rainy season. Almost all the families of the SCs in our village are doubling as tenants for somebody or the other. While the older male works as the tenant, his wife would go for work as a daily wage earner, the son would be part of a youth gang who do work on “contract” earning a fast buck (and blowing it up partly). Girls, especially, do a lot of domestic chores and are ready for agriculture work at the tender age of 10 to 12. Most of them are married off by the time they are 14-16, some just after reaching puberty. People are afraid of illegal sex before marriage. What is surprising is that marriage seems a sort of license. Extra marital affairs, flings, are very common, not taken too seriously! This is the case even among the farmers, although the frequency is higher among the workers and goes by the caste of the people involved as well.

Four-five decades ago, my grand father and later uncle had around 10 farm servants working throughout the year. One to look after the hundred odd sheep, one for the 20-40 buffaloes, one for the 40-60 cows, four pairs of bullocks, looked after by at least two persons, one or two in the kitchen. There was hardly any tenancy. All agriculture work would be done with farm servants and hired labour. Unless a severe drought struck (once in 15-20 years) there was always work and always food. No one needed to go hungry. The food consisted of ragi and rice balls with some pickle or hot curry to gulp it down with some buttermilk at times, especially in summer. There was also jowar and other millets which were more cumbersome to cook. Even smaller farmers had paid servants working on yearly basis. The children would start as cattle rearers and graduate finally to ploughing with bullocks and preparing the paddy fields – the toughest jobs. The forest was plenty and lot of things could be obtained “free” - fire wood, bamboo and wood for the housing. The forest had always been taken for granted.